Richards was right, of course. Andrew caused about $16 billion in insured damages that triggered more than 600,000 claims. Eleven insurance companies went belly up, and the finances of dozens of others were shaken.

Continued from Part 1

Tens of thousands of policyholders were left stranded. While those in Andrew's relatively narrow path began rebuilding, Allstate announced plans to cancel 300,000 of its 1.1 million policies in Florida and raise rates 32 percent, a plan it scaled back after furious protests from homeowners.

Richards said the relationship between insurance companies and homeowners began to sour.

“After Hugo, lawsuits against insurance companies were in the dozens, but after Andrew, they were in the thousands. It shows there was a different climate after Andrew.”

Hurricane Andrew was particularly helpful, though, to a woman in Boston named Karen Clark, head of a little-known company called Applied Insurance Research.

While other insurers had predicted potential insurance losses in the low billions of dollars, Clark had warned that a major South Florida storm could generate a $30 billion insurance industry hit.

Her calculations were based on a novel way of looking at risk.

In the past, insurance companies tallied potential losses in a particular area and stopped writing new policies when they felt their exposure was too high. But Clark questioned how you could truly understand risk without knowing your odds of being harmed.

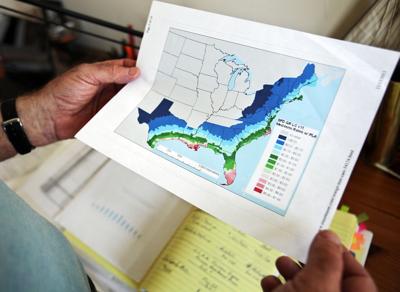

So she plugged historical data on hurricane strikes into computer programs along with data about homes and buildings — potential losses for anyone who insured these structures.

Then she ran computer simulations of what might happen in various scenarios.

Her success in predicting losses before Andrew launched the new industry of “catastrophe modeling.” Other companies soon created their own models, which became known in the industry as “black boxes” because their algorithms and inputs were kept secret for competitive reasons.

These mysterious black boxes would increasingly determine what homeowners from the Gulf Coast to New England shelled out in premiums.

During his career as a corporate executive, Daryl Ferguson had moved to different cities across the country, but when he finally retired on a bluff overlooking the Whale Branch River near Beaufort, he thought his property insurance seemed unusually high.

Now, with his new understanding of hurricane risks in South Carolina, he was even more convinced that his rates were out of whack.

“My insurance company, USAA, is terrific, so I did a test.” He asked company officials how much it would cost to insure a newly built $400,000 home in Gulfport, Miss., versus one in Beaufort County.

Gulfport had been hit hard by Katrina and Rita and is considered particularly vulnerable to hurricanes. “I couldn't believe what they told me.” His hypothetical Gulfport bill would be one-third the price of his Beaufort premium. “I turned to my wife and said, 'This is like Sherlock Holmes; one question leads to another.'?”

Ferguson had stumbled onto something. The average premium for $400,000 homes in South Carolina was the seventh highest in the nation, roughly the same as tornado-prone Oklahoma, according to the National Association of Insurance Commissioners.

“I was shocked,” Ferguson said. “My first instinct was to go to the Department of Insurance and ask them why they're approving these rates, but I decided to do some homework first.”

He began looking for Martin Simons.

Few people outside the insurance industry knew more about the black boxes than Simons, a bookish man with a scraggly salt-and-pepper beard who, unknown to homeowners, had long had a major impact on what they paid in insurance.

Between 1985 and 1997, Simons had been deputy director and chief actuary for the state Department of Insurance. In that capacity he had forced some insurers to reduce rates when their profits were too high and urged others to raise rates when his analyses showed they were too low. He left the agency when he felt state leaders had become too anti-regulation, and he had gone on to build a national reputation in the arcane world of actuarial analyses.

When Florida regulators established the nation's first independent panel to review how computer models affect rates, they hired Simons. He later did work for Maryland and California, and conveniently lived in Columbia.

Ferguson met Simons for lunch at the Chili's restaurant next to Simons' granddaughter's auto repair shop in Summerville.

“The first words he said to me were, 'Daryl, I know what you want.'” Ferguson was puzzled. “Then he said, 'You want to know why the Department of Insurance doesn't regulate its homeowner industry?' It was exactly what I wanted to know.”

Simons had long lamented the lack of transparency about the catastrophe models. In 2003, State Farm requested a 29 percent increase in its rates. This hike would ripple across the state because State Farm controls about 25 percent of the homeowner's insurance market.

State Farm justified the increase in part because of results from the black boxes.

At the time, the state Department of Consumer Affairs was charged with reviewing rate increases, and the agency hired Simons to scrutinize State Farm's proposal. In sworn testimony before the hearing, Simons said the request was “seriously flawed,” largely in part because state regulators knew nothing about how catastrophe models work.

The stakes were huge, he testified: Unscrupulous insurers theoretically could choose a model to set rates as high as possible. Or they could use a model's calculations to justify reduced rates to undercut their competitors, putting the company at risk if a storm struck.

“Eventually all property insurance premiums for hurricane coverage in South Carolina will be determined using the outputs of stochastic computer hurricane simulation models,” he testified, adding that the insurance industry also uses these black boxes to assess terrorism risks and in health, auto and life insurance calculations.

How the state deals with these models “will impact every citizen in this state.”

Minutes before the rate case was set to begin, State Farm settled for a 19 percent increase and an agreement that it wouldn't oppose an independent panel to examine catastrophe models.

That review didn't happen. The Department of Insurance, with money from the S.C. Sea Grant Consortium, asked three experts to look at the models. One was Peter Sparks, a noted civil engineering professor at Clemson University who had done extensive studies about wind speeds and damage.

Sparks has found that the National Hurricane Center tends to overstate wind speeds inland, and that “an unwise modeler using National Hurricane Center reports could easily get a distorted picture of the wind climate and recommend rates far higher than justified.”

He said that when he and the other panel members asked the modeling companies for a look at the assumptions built into their black boxes, “They said that the information was proprietary and would not disclose their methods. We said we could not judge the soundness of them, and the Department of Insurance eventually abandoned the whole exercise.”

Meanwhile, the General Assembly eviscerated the budget of the S.C. Department of Consumer Affairs, the government's main insurance watchdog.

The department lost half of its employees over the past five years; today, it has about 30 staff members to cover thousands of consumer complaints and insurance issues, one-third the roster of the University of South Carolina football team.

In 2007, amid threats that insurance companies would abandon coastal areas, lawmakers also stripped the agency of its ability to challenge rate increases below 7 percent. That meant, in effect, that an insurance company could raise rates almost at will as long as its average increase was below 7 percent. “We've had a lot of 6.9 percent rate increases since then,” said Elliott Elam, the state's consumer advocate.

To Simons, insurance rates involve finding a delicate balance between a company's capacity to make money and a homeowner's ability to pay. And in the absence of a serious review of these black boxes, he feared that homeowners on the coast are getting crushed.

Ferguson said alarm bells went off when he heard Simons talk about this imbalance.

As a former CEO of large and heavily regulated utilities, “I had first-hand knowledge about what happens when a state doesn't regulate,” he said. It meant millions of dollars could be added to the company's bottom line, and millions subtracted from customers' pockets.

Experts acknowledge that no computer model can predict the future, but a new iteration of computer models has taken a step in that direction. These new models use data on warming oceans and other variables to forecast potential hurricane losses in a five-year period.

In the mid-2000s, these models predicted a major increase in hurricane losses, and as a result, insurance companies sought rate increases and pulled out of coastal areas in South Carolina and elsewhere, triggering what was widely described as an “insurance crisis.”

So far, the predictions of these new models haven't panned out, said Karen Clark, the architect of the original black box. In a study, she found that they overestimated losses by as much as $53 billion.

Clark told The Post and Courier that catastrophe models are useful but crude tools, and that it makes little sense to predict hurricane losses in the near term when meteorologists struggle to predict how many storms might form in the coming hurricane season.

“Trying to project hurricane experience over a short-term horizon is inherently flawed,” she said.

Then again, the use of catastrophe models has “added a degree of stability to the insurance market that wasn't there before them,” said Michael Young, a senior director with Risk Management Solutions, the largest of the modeling companies. The industry's performance is proof, he and other insurance experts said.

While many companies went belly-up after Hurricane Andrew, only one went under after the devastating hurricanes in 2004 and 2005. Last year, despite horrific losses worldwide and in the United States, the U.S. property and casualty industry made $22 billion in profits.

In Beaufort, Ferguson pages through notebooks he has compiled during his investigation. From his upstairs window, the marsh in the Whale Branch River shimmers in the heat. He estimates that he has spent 2,000 hours on this project, time that gave him new appreciation of the mysteries of the Lowcountry and fewer reasons to fear that a hurricane will blow it all away.

“We have plenty of time to get out of the way if a storm does come our way, so the risk isn't about people anymore; it's about property.” As he grew less fearful about hurricane season, he thought about the opportunities this new perspective presents: How a regional campaign to promote Lowcountry tourism in the fall could generate thousands of new jobs, how an in-depth look at insurance rates by state regulators could stimulate the economy like a tax cut.

With homeowners shelling out $1.3 billion in premiums, even a small percentage reduction could mean tens of millions of dollars.

But as stores put up hurricane displays, and emergency officials issue fresh warnings to get ready for the hurricane season, the questions in Ferguson's mind continue to spin, especially when he goes to a picnic on Memorial Day and hears what happened to his friends.

They live in Bull Point, a subdivision well inland from Beaufort, and they had just received a letter from their insurance company canceling their insurance effective Aug. 29. The reason: catastrophic wind exposure.

“Why?” he asked out loud after seeing the letter. The company hadn't explained its reasoning, or given his friends a chance to discuss the issue. “Overall, this looks like a monopoly gone wild,” he said, “and the only one that loses is the customer.”